The story has been told, and retold,

beginning on that fantastic April 18, 1943. Papers

all across the U.S., as well as elsewhere, trumpeted

the story of how the 57th downed at least 74 Axis

planes (while losing not more than 6) and causing

an estimated equal number to crash land to avoid

being shot down. Even though great happenings

were expected from the 57th, which had become

known as “America’s Flying Circus”,

that Palm Sunday event was beyond expectations

even for them. The story got the front-page headlines

from “Stars and Stripes”, the “Tripoli

Times”, the “Egyptian Mail”

and “Yank”. “Yank,” insisted

on giving the name Charles to Col. Arthur Salisbury

in both is July and September issues relating

the story. A book, “Mediterranean Sweep”

devoted a chapter to the story. The story surfaced

in later years such as in the men’s magazine

“Stag.” The members of the Group called

it a “goose shoot”; the writers glamorized

it with the name “The Palm Sunday Massacre.”

The official reports are usually very austere

and brief such as the Groups operational control;

RAF Group 211’s report a well as the War

Department’s public relations release. The

9th Air Force in its publication at that time

“Desert Campaign” tells it quite eloquently:

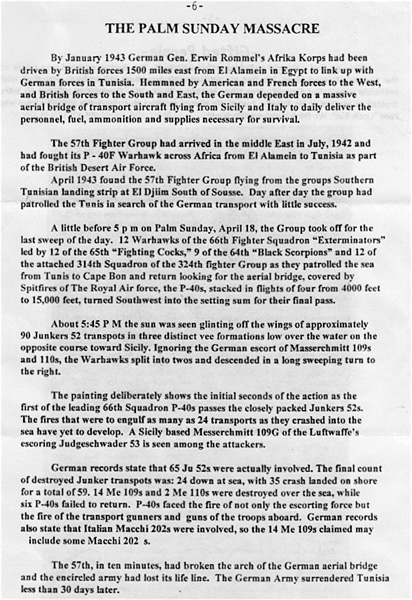

Through the April skies over Cape

Bon that Palm Sunday afternoon droned a hundred

enemy transports escorted by upwards of fifty

fighters, all flying perfect formation. In a matter

of moments that drone welled to thunder. The armada

had met the Fifty-seventh on patrol out of its

current base, El Djem, Tunisia. Forty-six Warhawks

with RAF Spitfires flying top cover swept in with

blazing guns and the air became a whirling, screaming

mass of diving planes and gunfire. Junkers transports

blew up in mid air; Junkers dived into the sea

and on to the beaches, some crash-landing. Some

dropped like spent rockets, streaming smoke; some

fluttered down in crazy-control like falling leaves;

some landed in the water and bounced like skipped

stones. Then the Messerschmitt fighters began

falling through from above and it became a problem

of dodging falling enemies while shooting others

down. So closely packed and disorganized was the

mass that it became difficult to keep clear of

friendly fire.

The beaches and the surf below became littered

with wreckage. Troops jumped from some of the

planes as they neared the water, others poured

out of crash landings on the beach. Eighty per

cent of the wrecked planes were flamers and at

one spot the sea beneath became a sheet of fire.

Up above the Spits fanned the ME-109 and 110’s

down to the Warhawks’ fighting level and

for fifteen blazing minutes hell reigned above

and debris rained below. The Black Scorpions,

Fighting Cocks, Exterminators, squadrons of the

57th well earned their names and the less experienced

Yellow Diamonds showed what they had learned with

a little plus over their mentors.

When the Warhawks had exhausted their fuel margins

and had to turn homeward, the score stood at 75

planes destroyed, including 58 of the three-engined

troop carrying JU-52’s and 14 high flying

ME-109’s and 110’s and one Bf 109

and two Italian fighters who blundered up to the

level of the Spits. Of eight American pilots missing

after the battle two were reported the next day

to have landed safely in friendly territory.

The few terse phrases of the routine mission report

with comment in the language peculiar to American

fighter pilots lends graphic detail to the story.

The mission report, a typical one, came from the

Commanding Officer of the 57th, Colonel Arthur

G. Salisbury. An added touch was this aside from

the youthful commander. “I’ve been

telling everyone that the 57th is the greatest

bunch of fliers in the desert, but now I won’t

have to make that speil - everyone knows they

are the greatest. Boy, am I happy!” The

report continues: Mission time 16.50-19.05, 47

Warhawks ordered up on fighter sweep over enemy

lines. One a-c returned early.

…Formation flew to point X, picked up cover,

then NW to point A and along coast to point B,

where 100 plus tri-motored transports were encountered

(some Savoias but mostly JU-52’s) flying

on deck in NE direction escorted by 50 plus ME-109’s

and ME-110’s flying from 4,000 down to deck.

Enemy a-c were engaged…

“Look around and take it easy, boys”

came the voice of Captain James G. ‘Big

Jim’ Curl on the interplane radio. “It

may be a booby.” Curl, who is from Columbus,

Ohio, was leading the 47-plane formation. He briefly

searched the sky overhead to be sure the Spitfire

cover was there, then on the radio again, this

time less cautious and with a note of glee: “Juicy,

juicy, juicy. Let’s get ‘em boys.”

Curl’s wingman reported; “After Curl

gave the warning we went down, the two of us,

full gun. The transports, meanwhile, must have

seen us, for they went ahead wide open. This sudden

spurt left twelve of fifteen stragglers behind

the last V. Curl and I hit those. I fired on the

first plane, which came into my sights. A short

burst left his port engine burning. The flame

trailed the whole length of the plane. The center

or nose engine was also on fire. The Warhawks

have three fifty-caliber guns in each wing and

throw a lot of lead. I lost Curl during this pass.

As I pulled up I saw the Junkers stall and hit

the water with a big splash. I made a quick climbing

turn and got on the tail of another transport

- and then pulled away suddenly when I mistook

antother Warhawk for a Jerry.

“All three Vs of the transports were turning

toward land by now. I got my second Junkers near

the beach – it crashed into the surf and

exploded. Another crashed near it at the same

time and I saw a Warhawk hit the water. There

weren’t any chutes in the air. I don’t

think the transports carried any. I had an inconclusive

scrap with a Me-109 before I ran out of ammunition

and found myself low on gas. That ended my part

of the scrap.”

…Enemy a-c apparently not aware our presence

until we struck… “They were flying

the most beautiful formation I’ve ever seen,”

was the comment of Lieut. William B. Campbell

of Blissfield, Mich. “It seemed like the

a shame to break it up. Reminded me of a beautiful

propaganda film. They seemed to be without a leader

after our first attack and just continued to fly

straight ahead. That was suicide.”

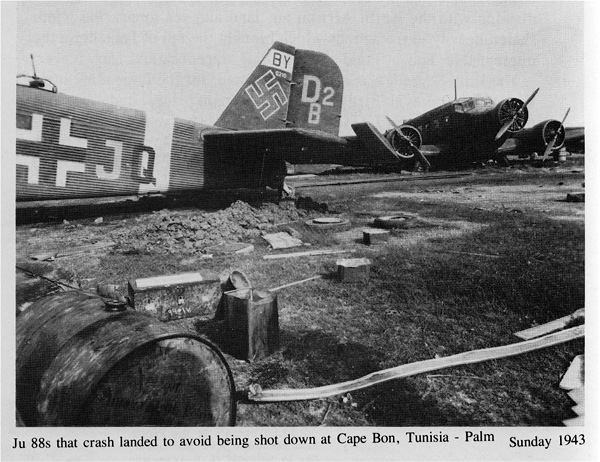

…Some enemy a-c believed to have bellied

in at point C, apparently a landing ground. Many

a-c, 20 to 40 JU-52’s were seen to belly

land on beach Cape Bon. Between 50 and 60 fires

were observed in vicinity of beach…

“There were so many targets in the air and

crashing into the deck, and so many of us after

them, I was afraid I was going to be left out,”

said Lieut. MacArthur Powers of Inwood, N.Y. “We

almost fought among ourselves to get to the enemy.”

Powers shot down four JU-52’s and an ME-109

within 20 minutes to cinch the title “ace”.

…A considerable number of personnel, many

believed to be troops were reported by pilots

to have leaped out of crashed e-a that bellied

in…

Lieut. Harry Stanford of Munising, Mich., who

accounted for three JU-52’s corroborated

that report. He had a look at the scurrying personnel

from deck level, and this is how he got there:

“I got two transports with my guns, then

drove on a third. But when I pressed the tit nothing

happened; my guns were jammed. It made me so damn

mad when the guns didn’t bark I decided

to get that third guy if I had to dive him into

the drink. Sure enough, he saw me coming and dived

to get away, and he couldn’t pull out. He

went in with a tremendous splash. I skimmed along

the deck and sailed for home. You should have

seen those Jerries scram from the wrecks on the

beach.”

…The pilots of the ME-109’s were considered

to have flown their a-c in a confused and inferior

fashion after the engagement began, probably due

to the low altitude and disorganization caused

by the Spitfire attacks above.

“The ME’s were all messed up,”

said Lieut. R.J. Byrne of St. Louis, MO., who

shot down three of them, from his position in

top cover with the Spitfires. “I got three

of them, but that isn’t anything. Wait until

the rest of the gang gets back. I had a ringside

seat for the whole show. All you could see were

those big ships coming apart in the air, plunging

into the sea and crashing in flames on the beach.

Their fighters couldn’t get in to bother

our ball carriers at all.”

…80 per cent of the JU-52’s destroyed

are estimated to have been flamers and very few

transports, if any, left the target area…

Captain Roy Whittaker was leading an element of

the Fighting Cocks, the second squadron to go

down into the melee: “I attacked the JU-52’s

from astern at high speed and fired at two planes

in the leading formation. The bursts were short

and the only effect I saw was pieces flying off

the cabin of the second ship. I pulled away and

circled to the right and made my second attack.

I fired two bursts into two more 52’s-again

in the leading formation. They both burst into

flames. The second flew a little distance and

then crashed into the water. I lost sight of the

first and didn’t see it hit. I then made

a third pass and sent a good burst into the left

of the formation, at another Junkers. As I pulled

away it crashed into the water. By that time the

Me-109’s were among us. As I pulled up to

the left I saw a 109 dive through an element of

the four Warhawks and I tagged on his underside

and gave him a long burst in the belly. He crashed

into the sea from a thousand feet.

“I then joined up with some Warhawks which

were luffberrying with six Me-109’s. I met

one of these fighters with a quartering attack

and hit him with a short burst. Pieces flew from

the plane and he started smoking, but he climbed

out of the fight.” Captain Whittaker claimed

three JU-52’s and one Me-109 destroyed:

One Ju-52 and one Me-109 damaged to run his victory

string to seven: “It was a pilot’s

dream. I’ve never seen such a complete massacre

of the enemy in my life. I was afraid someone

would wake me up.”

Lieutenant Richard Hunziker, another Fighting

Cock pilot on his second combat mission spied

what looked like “… a thousand black

beetles crawling over the water.” I was

flying wing ship on Major Thomas, who was leading

our squadron. On our first pass I was so excited

I started firing early. I could see the shorts

kicking up the water. Then they hit the tail of

a JU-52 and crawled up the fuselage. This ship

was near the front of the first V. As I went after

it I realized I was being shot at from transports

on both sides. It looked as though they were blinking

red flashlights at me from the windows. Tommy-guns,

probably. The ship I was firing at hit the water

in a great sheet of spray and then exploded. As

I pulled away I could see figures struggling away

from what was left of the plane.

“Id lost Major Thomas. There were so many

Warhawks diving, climbing and attacking that it

was difficult to keep out of the way of your own

planes. I made a circle and then heard someone

say, over the radio: “There’s M-109’s

up here – come up and help us.” So

I climbed to 5000 and flubbed around among the

dogfights, not knowing just what to do. Finally

I got on the tail of a 109. As I was closing I

noticed golf balls streaming past me on both sides.

That meant there was another enemy fighter behind

me, firing at me with his 20-millimeter cannon.

“So I took evasive action. That brought

me over the shoreline, where I hooked on to another

enemy fighter. My first squirt hit near the nose

of the ship. Pieces flew off and he went into

a steep dive. I followed him closely, still firing,

until he crashed in a green field with a big splash

of smoke and flame. Then I heard them giving instructions

to reform.”

…The final note on the mission report, except

the full box score of participating pilots, was

this: “This organization realizes the tremendously

important part played by the Spitfire cover, which

shot down three enemy fighters in the melee in

our last mission of the day. For the splendid

cover provided and the job of keeping enemy fighters,

although greatly outnumbered, occupied throughout

the battle, go our heartiest thanks.”

Describing the engagement, Captain Curl said,

“When I first saw the Jerry planes they

were right beneath us, about 4000 feet down. Camouflaged

as they were with green coloring, it was rather

difficult to distinguish the transports against

the sea. When we got nearer they looked just like

a huge gaggle of geese for they were traveling

in perfect ‘V’ formation, tightly

packed. The boys simply cut loose and shot the

daylights out of them. What concerned our pilots

most was the danger of hitting our own aircraft,

for the concentration of fire was terrific and

the air was filled with whistling and turning

machines. There were cases of pilots missing the

transport they aimed at and hitting the one behind.

It was as fantastic as that, you just could not

miss. There was no real fighter opposition because

the British Spitfires that were flying our top

cover did a grand job of keeping the Messerschmitts

so busy that they could not interfere with our

attack to any extent.”

Captain Curl said that the enemy ships were so

tightly packed that he sometimes had three in

his sights at the same time and that he saw one

of his squadron mates get tow of them with a single

burst from his machine gun. Capt. Curl, having

been previously recommended, became Major Curl

the day after be became Ace in this battle by

bagging his third, fourth and fifth enemy planes:

Two Junkers and a Messerschmitt.

Returning Warhawks brought back to base that Sunday

evening three other newly made aces and a big

and glorious job for the artistic crewman who

paints victory trophies on fuselages. The aces

were: Lieut. McArthur Robert Powers, Inwood, L.I.,

New York, who shot down four Ju-52’s, and

one ME-109 to bring his total to seven enemy aircraft

destroyed; Lieut. Richard E. Duffey, Walled Lake,

Mich., who shot down five JU-52’s and damaged

an ME-109 and Capt. Roy E. Whittaker, Knoxville,

Tenn., who was credited with three JU-52’s

destroyed and one damaged and one ME-109 destroyed

to bring his total to seven.

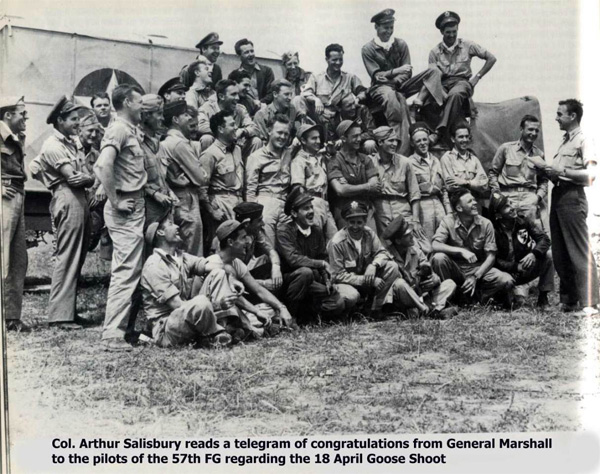

Praise came from high places and so did enemy

bombs. While General Brereton was receiving congratulations

for the men of the 57th those men were dodging

bombs back at their base near el Djem. For two

sleepless nights, April 19 and 20, Jerry pounded

their home field in angry retaliation. A much-decorated

pilot, Lieut. Allen H. Smith, was killed by a

bomb fragment and there were seven men injured.

Three aircraft were hit; trucks and trailers damaged,

tentage shredded and personal belongings scattered,

buried and destroyed. Slit trenches on those nights

more than earned the hard labor, which went into

their digging. The next day the 57th moved even

closer to Jerry, but he didn’t return. Praise

came from many places-two such being from General

Byerly of Rear Army Headquarters and General George

Marshall, Chief of Staff, U.S. Army.

|

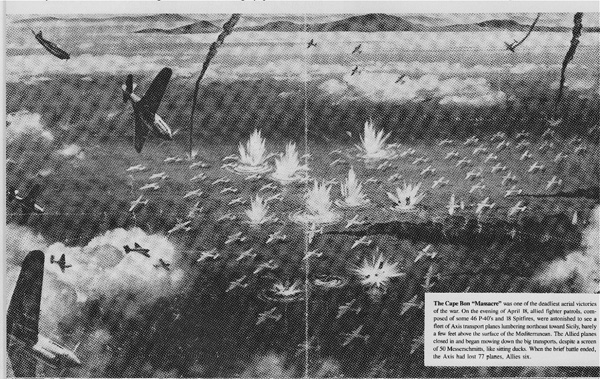

Short description of the battle

which also tells us what is

going on in the painting below.

Painting of "Goose Shoot''

of April 18, 1943 by artist Keith Ferris.

Painting hangs in the 57th Fighter Group Museum/Memorial,

New England

Air Museum, Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks,

Connecticut. Pic Mark O'Boyle

From Wayne S. Dodds

From Wayne S. Dodds

From Wayne S. Dodds

From Wayne S. Dodds

|